Let's Talk about Communication

It's not just a nice to have

In last week’s newsletter, I claimed that culture and communication are incredibly closely intertwined, and that by improving communication, you can improve culture.

I hope I’ve persuaded you that that is the case, but even assuming I have, it raises another set of questions. What’s happened to our ability to communicate at work? Can it be improved? And if so, how do we improve it?

Let’s take a brisk tour through each of those questions.

What’s happened to our ability to communicate at work?

Like any durable skill, the single biggest factor that determines our competency is practice - both inside and outside of work. So if you see people finding it challenging to have meaningful conversations or problem-solve together, you can justifiably blame it on a severe case of modern life.

Almost all of us have fewer real-time, meaningful conversations. When we do communicate, it's increasingly shallow and asynchronous. Text messages replace phone calls. Emails substitute for meetings. Voice notes stand in for actual dialogue. In our most recent study of workers, the majority shared that the “person” they communicate with most daily is ChatGPT.

Like any muscle, our communication skills atrophy without use. We're becoming less comfortable with real-time, unscripted human interaction. Add to this our immersion in digital worlds - audiobooks, video games, endless scrolling, all at the expense of the real world, and our interpersonal communication muscles are genuinely weakening, at a societal level.

Then there is the question of who we are talking to. Social media has enabled us to organize into communities around shared viewpoints, isolating us from dissent. So we are losing the ability to engage productively with people who see things differently. When every conversation happens in an echo chamber, we never develop the skills to navigate disagreement.

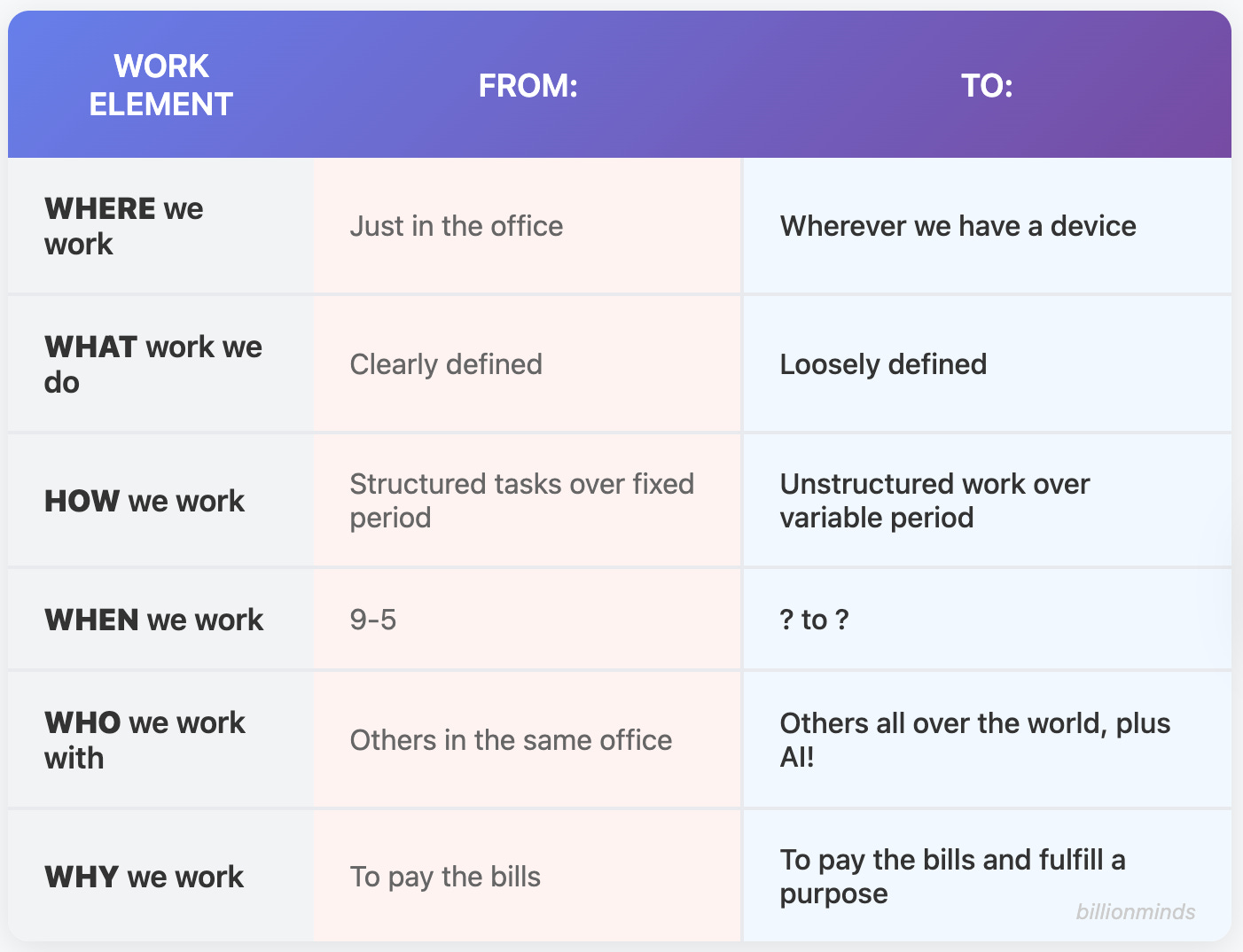

So that’s the background, but our work environments are not helping either. Here’s a table I often present to companies as a reminder of just how much work has changed in the last couple of decades:

Let’s face it, that’s a LOT of change over a short period of time. And it’s adding to the atrophy of our communication muscles. As I’ve mentioned before, in our work we’ve found several examples of employees who have worked for years sitting next to a colleague that they have never spoken to. Just another example of how we are becoming locally disconnected as we get more globally connected.

But there is another aspect of our work environments that is also affecting our ability to communicate - the breakdown in trust. Last week, I examined a couple of ways in which communication and trust are intertwined, but there is a third - the way trust affects the depth of communication. In low-trust environments, communication becomes significantly shallower as the parties avoid tough conversations. Without trust, communication becomes performative rather than genuine. People often say what they think others want to hear, rather than what needs to be said.

Pull all this together, and in the last 20 years or so, we’ve created climates where people communicate less often, less effectively, and with less meaning.

How Much Does this Matter?

It turns out this is all very important because communication is the vehicle through which collaboration occurs and culture develops. Culture doesn't spread through mission statements or town halls. It spreads through managers who can say, "I noticed you handled that situation differently than we discussed," and employees who feel able to respond honestly. It spreads through colleagues who can disagree productively and teammates who can give each other genuine feedback.

The reality is that companies with the strongest cultures aren't those with the most sophisticated culture programs. They're the ones where people actually talk to each other about what matters. It’s as simple as that.

But none of this happens automatically anymore. The old assumption that people would naturally develop these skills through experience no longer holds, because work and society have changed so much. We have to be intentional about building communication capabilities.

The good news is that most organizations intrinsically understand the vital importance of communication skills, even if they’ve never held a meeting on it. We know this because it’s the number one durable skill requested in job postings.

The Specific Skills to Rebuild

If we are to rebuild communication skills, we need to do so in a way that matches how work happens these days. At an individual level, people need to be great at succinct, clear written communications, like the ones espoused by the folks at Smart Brevity, but they ALSO need to be able to go deep where necessary. They need to be well prepared for presenting at the daily standup or the team meeting, but they also need to be able to cope with the ad-hoc unexpected corridor request. They need to be a good “prompt engineer” when talking to AI, but then relate to a real human when the time arises.

That’s a lot. In our work with individual contributors and leaders, we break communication down to something we call the 4 Rs. Here they are:

Real: Is what you're communicating accurate? In an era of information overload, getting your facts straight is the foundation. This includes knowing when you don't know something and communicating that.

Receivable: Can others actually understand what you're sending? This isn't just about clarity - it's about considering your audience's context, communication style, and current mental bandwidth. Something might be "clear" to you, but not receivable if you're using jargon with a non-technical audience.

Relevant: Are you giving them information they actually need, when they need it? Or are you explaining around topics rather than directly addressing the question asked?

Resonant: Do they connect intellectually and emotionally with what you're saying? This is where communication moves beyond information transfer to relationship building and genuine influence.

How to Rebuild Them

This is the area that many, even most, organizations get wrong. Perhaps they think everything will be solved by pulling people back into the office, even though the people who sit next to each other usually aren’t closely collaborating in real time. Or they create elaborate mentoring programs that ignore entirely the communication skills of mentors. Or (and this is my personal “favorite”) they institute forced fun initiatives in the aim of getting employees to bond over activities they have no interest in.

There are three elements that we’ve found to be essential to truly rebuild communication skills. They form a cornerstone of all our durable skills work, but are particularly important when it comes to this skill.

Safe Practice Environment

Your organization might invest heavily in manager training and in psychological safety initiatives. But does your organization feel completely safe? Almost certainly not.

40% of employees experience at least one layoff during their career. And over 70% have experienced toxic behavior from a colleague or boss that has made their work almost unbearable. Even if your company regularly appears on best places to work lists, it’s very likely that a proportion of employees right now are feeling deeply uncomfortable about their job, afraid of what it would be like to lose it, or afraid of showing up to do it.

But while the real world can be scary, simulation environments don’t have to be.

That, of course, is the theory behind flight simulators. Create an environment where people can fail and nobody gets hurt. And do so repeatedly until the failures are vanishingly rare.

As an organization, you can and should do work to create environments that are psychologically safe. But as you work on getting there, it’s vital to create safe practice environments. This allows participants to be comfortable failing and learning from it, which creates the perfect conditions for improving.

The setup here does not have to be elaborate. It can be as simple as using trusted third parties to conduct communication skills training, who are committed to not reporting back details of the training. As a matter of policy, we never report back details of individual practice, and it’s an essential component of our success.

Learning then Doing

This is a core tenet of most experiential learning. The idea is simple - understand a concept and then try it. Duolingo has its version, as does Simply Piano. And it’s part of all of our programs.

Both Learn and Do are necessary, as without a basic understanding of what you are working on (such as the four Rs), you cannot determine what you are trying to improve. And if you don’t practice, then all you have is knowledge, not an embedded capability.

In the case of communication, these practice cycles should span the various types of communication people often encounter at work, as well as the important scenarios they encounter less often. So think short form and long form, written and verbal, prepared and ad-hoc. Consider how the nature of what’s being communicated can change things. For example, someone may excel at communicating factual information but struggle with conveying employee performance issues.

To put this into perspective, our standard early in career durable skills program includes approximately 80 Learn/Do experiences, with 18 focusing on various aspects of communication - all essential, but all distinct.

Practice can be highly literal (for example, practicing communicating with a coach), but it can also be more reflective in nature (for example, critiquing one of your previous communications). Ideally, it will be a blend of the two.

Learn then DO should generally happen purely in a safe practice environment, but that’s ok, because of what comes next…

Doing then Learning

Doing then Learning is the sister approach to learning then doing, but it’s scarier because it happens in the real world.

The idea is really simple here. On a regular basis, after people exercise their communication skills in the real world, they stop, pause, and reflect on what they did well, what they did poorly, and how they could improve.

It’s amazing how rarely people do this. Most of us are too busy doing things to ever consider if we are doing them well. But regular reflection is hugely important to getting better.

To make it real, here’s an example from my own life. Humanity Working has a podcast, and every month or so, it features a guest, typically a published author. Even though these episodes are discussions about the human role in the workplace, I still strive to give the guests most of the talking time. After all, people hear from me every week!

Initially, I would just remind myself to shut up and listen, but about a year ago, I decided to reflect on how each interview went, including looking at data from the transcript to see how much of the conversation I was monopolizing. Over time, I reduced my talk time by more than 20% simply by observing and reflecting on it. This is Doing then Learning in action.

This is particularly vital when it comes to communication, because our research shows that of all the durable skills, it’s the one where people have the least self-awareness. So, reflect frequently on how you are communicating and ideally involve others in that activity, and you will get better.

The Path Forward

Look, this work is hard, but everything worthwhile is hard work. Building communication muscles requires the same commitment as building physical muscles - consistent practice, progressive challenge, and patience with the process. And while a learning and development strategy is essential, it’s not the full picture. Your organization needs the right infrastructure, policies, and support to make people want to work consistently on these skills.

But, organizations that invest in developing real communication skills - not just "communication training" but actual practice in safe environments - will have a significant advantage. They'll be able to maintain culture even in distributed, ambiguous work environments because their people can have the conversations that matter.

So here’s a question you can ask yourself, or of your organization. Are you treating communication as a nice-to-have soft skill or as the essential capability that enables almost everything else you are trying to achieve?

Ask that question, and be honest with your answer. Your future self will thank you.