What is an Expert?

Let's take a trip to 19th century Oxford to find out...

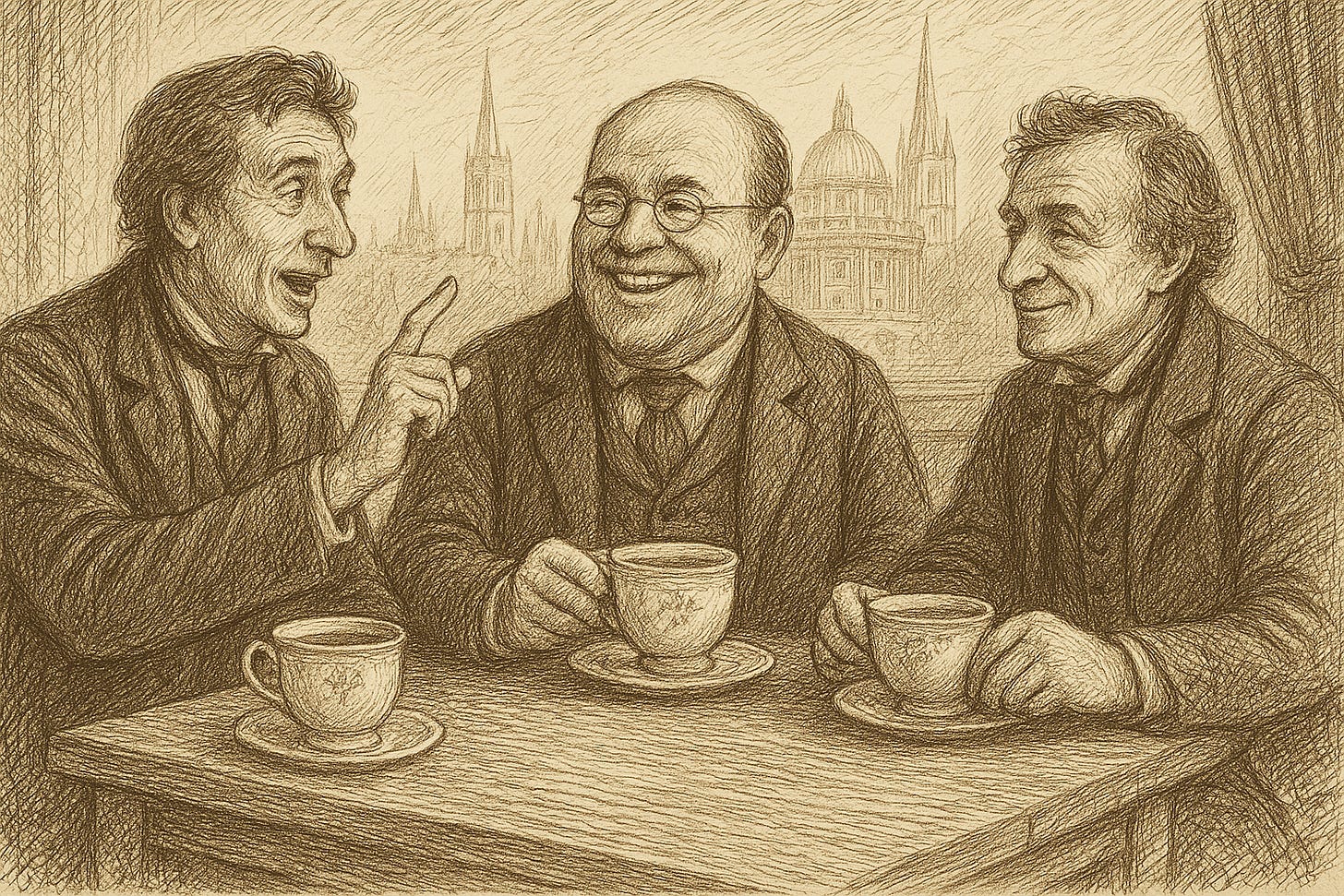

Oxford’s Grand Café, that venerable institution of the High Street, bore its years as a noble scholar often bears his: worn by time, weighty with learning, yet altogether rather magnificent. Brass fittings winked in the pale winter light, mirrors caught and multiplied the bustle of gowns and bicycles, and the strong scent of coffee clung to the air. At a corner table sat three regulars—Horace, Thomas, and Edward—engaged in earnest disputation, each holding his cup tightly before him, as though it were both shield and weapon in the fray.

“Look yonder, my friends!” declared Horace. “The Bodleian Library, the Radcliffe Camera, the Sheldonian Theatre. These are monuments to expertise, not idle ornaments of stone, but temples of diligence, learning and truth. What do they represent if not centuries of patient minds, each adding its modest taper to the greater lamp of knowledge until the flame burns high enough to banish ignorance? I cannot, by gazing at the heavens, prove that the Earth wheels around the Sun. I must rely upon those who know more, who have spent their lives in calculation and observation, so that others might be spared from error. Without experts, ignorance would reign over us, and we should forever be at the mercy of guesswork—stumbling through the shadows when a single candle may illuminate a multitude.”

Thomas stirred his coffee with deliberate force, as though the sugar must be subdued before his argument could be loosed.

“Yet ignorance still reigns, sir, and often under the proud banner of expertise itself! Recall the physicians who prescribed leeches for every malady, whose solemn nod could drain a man of both his strength and his purse. Recall the apothecaries, so confident in tone, with their powders and tinctures as poisonous as they were curative. Their titles dazzled the credulous crowd, yet their wisdom was scarcely greater than that of the hawker in the marketplace selling ‘cures’ in bottles that smelt suspiciously of gin. Even the finest scholar is confined—he may measure the pulse, weigh the draught, and still be blind to the grief of the family who bury their child beneath the weight of a doctrine proclaimed with certainty.”

Edward, tracing idle figures on his saucer, raised his head with sardonic amusement. “My dear fellows, the very word expertise is smoke—insubstantial, vanishing as soon as grasped. Consider the Black Death: learned men wrangled over miasmas and foul airs, debating with grave expressions while whole streets withered. And what broke the plague’s hold in London? Not their wisdom, but fire—merciless, accidental fire, which in a week accomplished what centuries of practice could not.

“Once it was sworn, with oaths and arguments, that the Sun revolved about our Earth; now the tale is reversed, and who is to say it shall not be reversed again? I should not be surprised if future ages discover vast realms of matter and energy, dark to us now, yet greater than anything our senses can seize. The expert of one century is too often the fool of the next.”

“And yet,” Thomas observed dryly, “fools are rarely unemployed. The world has a way of keeping them in business, especially when they call themselves learned.”

Horace bristled, leaning forward. “Would you abandon experts altogether? Even a one-eyed man is of use in the land of the blind. However incomplete his map, it is still a map. Without experts, we stumble in darkness, bereft even of the hope of progress. Consider the ordinary man placing his small savings into the care of a prudent and wise steward, who by steady guidance increases them year by year. That advantage compounds into prosperity, while the unaided neighbour risks all in folly. Shall we deny that such expertise is of service?”

Thomas straightened in his chair, his eyes glinting. “Yet what if the map leads astray? What if it serves the mapmaker’s purse more than the traveller’s path? Galen’s word bound medicine for a thousand years, his doctrines worshipped even as evidence lay contrary. His disciples dismissed every truth that did not fit their master’s scheme. To name a man an expert is too often to thrust a sceptre of power into his grasp, and thereby to see the multitude bend before him as if he were crowned by divine right.”

Edward’s laugh was soft but sharp. “Socrates would smile upon us here. His wisdom lay in knowing that he did not know. St Paul too: through a glass, darkly. Humility is the true companion of knowledge; presumption its oldest vice. Yet humility seldom bought a man a decent supper, which perhaps explains its rarity in professions that most depend upon the show of expertise.

The waiter passed with another pot, steam curling between them like a mischievous spirit. The bells of St Mary’s tolled, pressing their dispute into silence.

At last Horace murmured, “Perhaps the true expert is he who admits the limits of his sight.”

Thomas added gravely, “And perhaps the wisdom of the people is to question those who claim too much.”

Edward raised his cup. “Then in our quarrel, gentlemen, perhaps we have become ever so slightly more expert ourselves—though I cannot say the world is likely to pay us for it.”

They laughed, softly, and drank. And the Grand Café, which had heard centuries of such discourse, kept its counsel still.

Many thanks to my friend Sean Lemson, whose thoughts abound the term expert caused me to completely rewrite the newsletter I had planned on this topic. I only wish we could have the argument in person.

The Grand Cafe is still there Sean!

Oh, and if you would like to read something a big more practical about my thoughts on experts and expertise, check out this newsletter.

I promise to return to the 21st century next Thursday!