Young People Today! - Lessons Learned From Our Work with Early-in-Career Professionals

It turns out it's complicated...

“Young people of today think of nothing but themselves. They have no reverence for parents or old age. They are impatient of all restraint. They talk as if they know everything, and what passes for wisdom with us is foolishness with them.”

That quote is from Peter the Hermit, in 1274 - a man who would clearly not be considered a hermit by today’s definition.

Peter might have pioneered the “Young People Today” complaint, but a variant of it has occurred in every generation since. For hundreds of years, older generations have looked to the next wave of workers and felt a combination of frustration, or even panic, that the youngsters… just don’t get it.

But are things different now?

We’ve been studying this closely while developing our Early-in-Career Durable Skills Program, which is designed to help new professionals build the foundational skills to thrive today and over the long arc of their careers.

As we’ve built and rolled out the program, we’ve learned from employers and new employees about their experience of work, and this experience has led me to believe that two things are true at once.

1) Today’s early-in-career professionals have at least as much, or possibly more, potential than any prior generation.

2) Through no fault of their own, they have critical gaps in learning and experience that, if not addressed, could lead to significant societal challenges.

Let’s dive into the details.

A Growth Spurt Missed

Developmental psychologists from Piaget to Erikson have shown clearly that human development isn’t linear. It goes in spurts.

Language. Identity. Independence. Emotional fluency. Each emerges during specific windows of life—and when one window closes prematurely, the next doesn’t always open on time.

Now think about the key leaps for early-in-career professionals

The first two years of life: mobility, attachment, communication.

The first two years of puberty: self-agency, risk-taking, emotional range.

The first two years of college: curiosity, autonomy, experimentation.

The first two years of work: identity, confidence, fluency

From infancy to adolescence, from college to employment, there are certain windows where cognitive, emotional, and social development accelerates. These growth spurts build our sense of self, our ability to relate to others, and our comfort with uncertainty.

The current cohort of early-in-career professionals—college graduates who’ve entered the workforce in the last year or so—missed one of the most formative of these: the college growth spurt.

They were 18 or 19 during the height of COVID.

That means their transition into college—the period where independence is tested, social belonging is formed, and early adult identity takes root—happened in a period of isolation, uncertainty, and fear.

No clubs. No late-night debates. No casual experimentation or early leadership chances.

What a challenging start.

How this is showing up

When we developed our program, of course we spoke to learning and development leaders, but we also spoke to managers, college professors, and the early-in-career professionals themselves. Here’s a quick summary of these different viewpoints….

Managers

Managers see a group of people who lack some basic, durable skills they could previously take for granted. It shows up in many different ways, but here are some of the main challenges they talk to us about:

Hesitancy to ask questions

Discomfort with collaboration

Fragile confidence in ambiguity

Uneven energy

Low initiative

Unfortunately, some of the managers we’ve spoken to are at a loss as to what to do about this. They don’t feel qualified to teach these skills and certainly don’t have the time.

College Professors

Professors notice a shift, too, but from a different angle. While many students are passing (the effect on grades has been less significant than some expected), they see other differences in how students are showing up, or even if they are (college dropout rates are up).

In general, we are hearing that students who are more anxious, more risk-averse, and less socially engaged than cohorts from just a few years ago. There’s a reduction in peer-to-peer learning—the informal conversations, the healthy disagreements, the group study energy that once shaped campus life. Students often keep their heads down, get the work done, and move on. Which may sound fine—until you realize how much of modern work life depends on collaborating well with others.

Early-in-Career Professionals

And then there’s how it feels from the inside.

Many early-in-career professionals describe a strange dissonance: they’ve worked hard, they’re qualified on paper, but still feel behind. Like they missed a key part of the instruction manual that everyone else seems to have.

One person told us, “It’s like I was handed a jigsaw puzzle, but no box. I know the pieces go together, but I just don’t know what I’m building or if I’m even starting in the right corner.”

Apparently, some young people still do jigsaws.

And here’s another factor. The things that many older workers take for granted as benefits are double-edged swords for younger employees. A classic example is flexible work. Who doesn’t love that, right? Actually, many early-in-career professionals we spoke with thought of it as an extra burden. Several described situations where they were expected to adjust their schedules or work locations to accommodate others’ flexibility, without having much agency themselves. Freedom for one group can be instability for another.

Despite these different points of view, one thing came through loud and clear. This is not a group with a lack of talent. This is a group with a set of unique challenges that need to be addressed.

How NOT to Address These Challenges

So these are the most common views we heard of in terms of where things stand, but there are also, of course, no shortage of views on what to do about it. Before I get into exactly what I believe we should do, I’d like to address two points of view that I think are misguided

“Write them off, the next group will be better.”

“Don’t do anything, they’ll figure it out.”

Will the next group be better?

Well, let’s look at the next group.

Sure, they weren’t in college during the pandemic, but they had another growth spurt disrupted - high school. Think about all the stuff YOU figured out in high school, and who you would be today if you hadn’t figured those things out. Make no mistake - we aren’t looking at a few years of disruption here - a whole generation has been affected, and not just by the pandemic. This is the generation that has had to navigate the difficulties of a world where one wrong statement online could lead to years of misery. It’s not surprising if that translates to a lack of confidence and a desire to hide in plain sight.

And what about just leaving them to it to figure it out? Well, how did YOU figure things out at work? Chances are, you did a lot of learning by osmosis. From the person who put their arm around you the day you arrived, from the grizzled veteran in the corner who knew how things worked around here, from the co-worker for whom you could never do anything right, until one day you did.

A lot of learning by osmosis is dead, or at least on life support. And as we’ve discussed, dragging people back into the office doesn’t solve it. Work is distributed. People might be in the same room, but they are often not working with each other on the same stuff, and they are rarely available at the same time to talk about it.

The bottom line here is that if we want to address this, we have to be thoughtful about it, and we have to invest in this new generation of employees.

Here’s how:

How We DO Address It

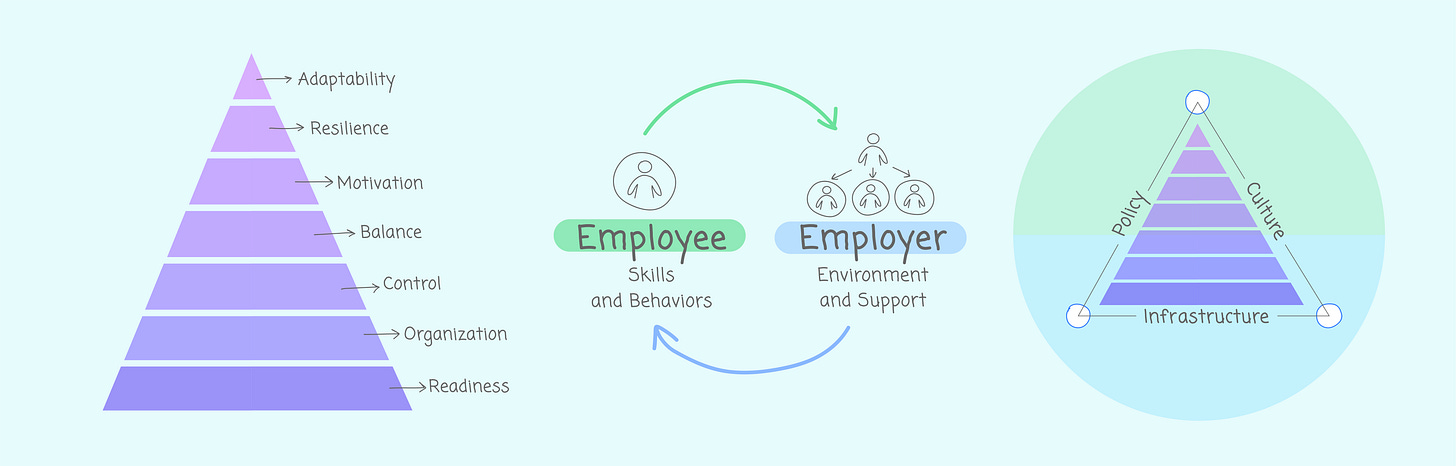

Meeting this moment needs way more than just giving the next generation of overwhelmed employees a copy of LinkedIn Learning. The focus needs to be on three areas:

Targeted Durable Skills Development for Employees

Our early-in-career program has ended up being quite different from the ones we target at mid-career employees and managers. For example, there is much more focus on being present in meetings, at mastering challenges like small talk, and on understanding how the older generation might perceive you.

But we’ve found our program also needs to recognize the unique skills that this generation brings, and build upon them. This is essential to help early in career employees feel they have a strong contribution to make, in a world where the future of work looks very uncertain.

Targeted Skills Development for Managers

Very early on in the development of our employee program, we saw that it wouldn’t do the job on its own. As tempting as it is to say that this is a problem just for early-in-career professionals, it’s also a problem for their managers. As I mentioned earlier, many feel highly disconnected to this new group. Our manager program (which launches in June), focuses on what it takes to create an environment where early in career professionals thrive, to the benefit of the whole team. It turns out that it takes a very different approach.

A Human-Centric Culture

This generation of employees will spend their entire careers in a world increasingly dominated by AI, robotics, and automation. The organizations that thrive will be the ones that figure out how to create the most effective human layer on top of that technology, centered on digital natives with highly honed human skills. Programs like the ones I’ve described here are part of that picture, but so is organizational design. These two things MUST work together, like in the picture below.

The Next Greatest Generation?

I said that today’s early-in-career professionals have at least as much or possibly more potential than any prior generation.

I genuinely believe that.

We tend to think of wisdom as the domain of the experienced. But wisdom is situational. It comes from contact with reality. There are many areas where early-in-career professionals have far more experience than we older folks. They’ve grown up in a digital-first world, formed identities in full view of the internet, and built social ecosystems we barely understand. They’ve developed instincts many of us are still struggling to hone: navigating ambiguity, managing public identity, and adapting in real time.

And the disruptions they’ve faced - the pandemic, social media, and a world of work where new technologies are closing down career paths almost in real time - are forging many of them with surprising levels of resilience.

This group of kids doesn’t need fixing, they need backing.

We’ve seen moments like this before in our history, most famously with The Greatest Generation. These young men and women faced trauma, disruption, and existential uncertainty—and emerged with resilience and clarity. They didn’t become great because life was easy. They became great because it wasn’t.

I think that can happen again. With this generation.